The Impacts of Climate Change on Incarcerated People in California State Prisons

By Aishah Abdala, Abhilasha Bhola, Guadalupe Gutierrez, Eric Henderson & Maura O’Neill

Produced by Master of Public Policy Graduate Students from the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs on behalf of the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights.

California is at the forefront of climate change. In the last ten years, the Golden State has experienced large-scale wildfires, surging temperatures, and devastating flooding, among other climate hazards, that have caused harm to human health and the natural environment.

This series of climate hazards has made it evident that the effects of climate change will continue to intensify, have the greatest impact on already vulnerable populations, and, most critically, the California carceral system is not prepared to respond to climate hazards in or near prisons.

Our first-of-its-kind report was developed through a mixed methods approach, using interviews with experts, a survey of nearly 600 currently incarcerated people in all 34 of California’s prison facilities, and a spatial analysis, we concluded that incarcerated people face unique challenges during climate hazards and thus must be included in any measure of vulnerability to ensure their safety and well-being.

Our report seeks to:

- Understand the risks that incarcerated people in California state prisons face as climate change related hazards such as wildfires, floods, and extreme temperatures, accelerate.

- Put forth policy solutions that protect taxpayer interests, keep incarcerated people safe, and ensure our government institutions are held accountable.

KEY FINDINGS

- Incarcerated people are distinctly vulnerable to climate hazards because they are entirely reliant upon the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) for preparedness, response, and recovery.

- CDCR prisons are highly susceptible to climate hazards because they are located in or near remote areas, have an aging infrastructure and population, and are overcrowded. As of January 2023, CDCR operated 34 prison facilities at 108.5% of its design capacity.

- CDCR provides the legislature and the public minimal information on its emergency preparedness. Furthermore, CDCR’s Department Operations Manual (DOM) describes evacuations in a limited way and details the agency’s procedures for fires and earthquakes so narrowly that it leaves many questions on how CDCR will keep people safe. The DOM also does not mention flooding, wildfires, or extreme temperatures, suggesting no emergency planning for these hazards has occurred.

- Lastly, other state carceral systems have failed to keep incarcerated people safe during a climate hazard. Our findings suggest California’s carceral emergency management system is set up to do the same.

“In 30-plus-years of incarceration, besides blackouts, I’ve endured earthquakes, heat waves, and flooding. I’ve made it through winters in which an extra blanket was the only thing that separated me from icy-cold air gushing into my small cramped cell. The world now recognizes that these weather extremes are the result of climate change. But, the effects of climate change on the millions [of] Americans behind bars often go unrecognized.” — Juan Moreno Haines

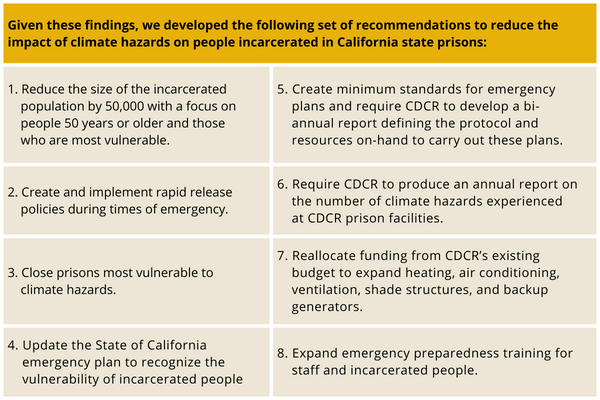

RECOMMENDATIONS

Juan Moreno Haines Incarcerated Journalist at San Quentin State Prison

For questions regarding the report, please email james@ellabakercenter.org.

For press inquiries, including all interview requests, please contact joshua@ellabakercenter.org.